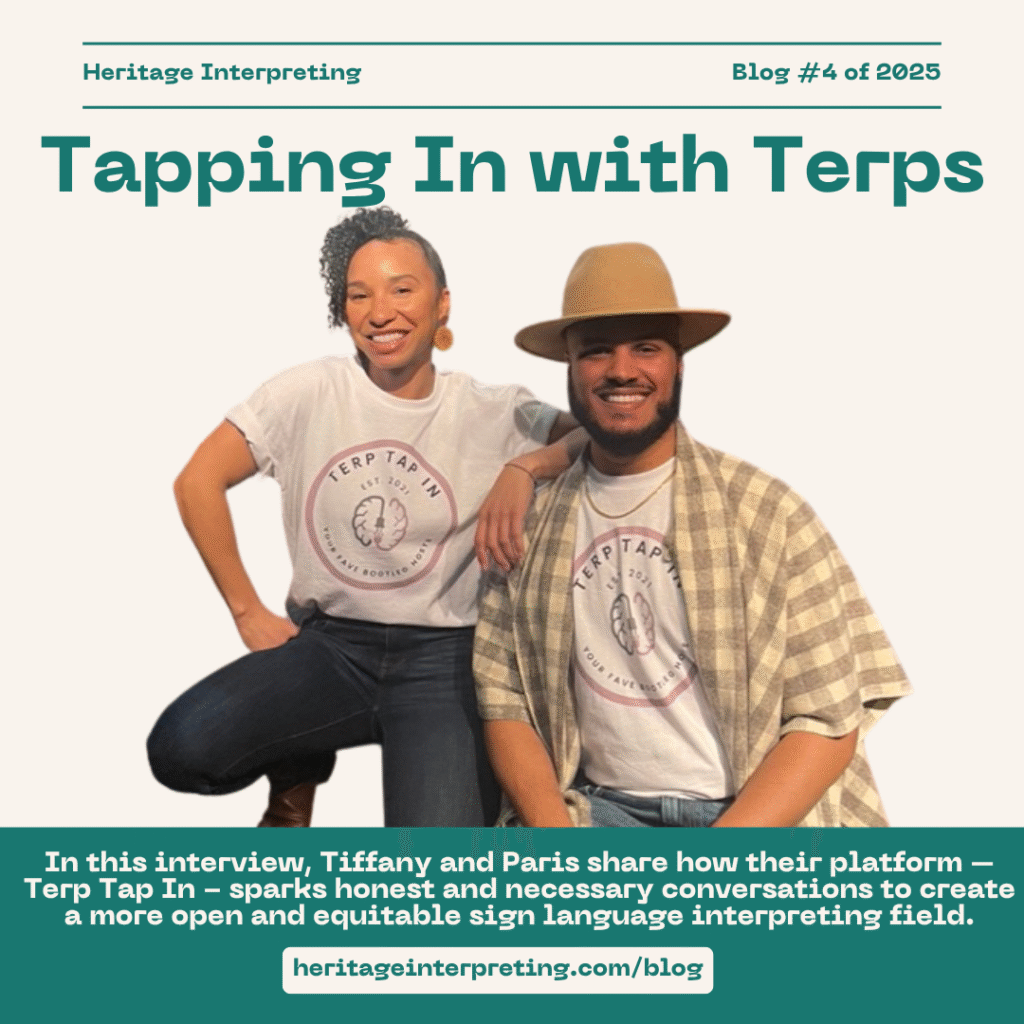

In this interview with Terp Tap In, a community-driven space to create conversations for all things interpreting, we connected with hosts Paris McTizic and Tiffany Hill to go over questions ranging from the uncertainty surrounding artificial intelligence in our interpreting field to navigating burnout and the emotional toll from interpreting assignments to redefining and practicing allyship and staying grounded in the sincerity and professionalism. Read more for their profound insight and reflections in responses to questions we asked below!

Is technology, like VRI (video remote interpreting) and AI (artificial intelligence), changing the interpreting landscape? Are we adapting fast enough? Should we push back on some of these technological advances?

Paris: AI is absolutely reshaping the interpreting landscape, whether we admit it or not. And no, as a field, we’re not moving nearly fast enough. That lag is what’s fueling tension, confusion, and even division in our community.

Part of the problem is how we frame it. Many interpreters are already using AI without realizing it—auto-captioning, predictive text, scheduling tools—but as soon as you slap the label “AI” on it, the fear kicks in. And to be fair, that fear isn’t random.

From the Deaf community’s side, the concern is real: that tech could strip away human interaction, empathy, and drag us back to old medicalized ideas of deafness. That’s not just paranoia, that’s history. And it deserves our respect.

Still, I don’t think the answer is to slam the brakes on AI. I think the answer is to meet the moment with power, not panic. If we’re part of the conversations as this tech is being built, we can demand ethical practices, push for equity, and maybe even fix problems that have haunted us for years—like interpreter shortages and inconsistent quality of services.

So yes, we should be cautious. And yes, we should absolutely push back when something feels extractive or out of step with our values. But we also need to lean in, stay informed, and claim our seat at the innovation table. Because if we’re not there, the table gets built without us.

What do you think the next generation of interpreters will eventually need that we didn’t have, didn’t address enough, or did/didn’t face?

Paris: We didn’t grow up learning in a virtual classroom, and that shaped how we connect and engage with the work. The next generation is walking in already fluent in Zoom, VRI, and whatever platform hasn’t even been invented yet. That’s a serious leg up.

But here’s the catch: interpreting isn’t just about catching words. It’s about presence. Reading the room. Feeling the vibe. Picking up when someone says “I’m fine” but their whole body is screaming otherwise. Technology can help, but it can’t teach you how to be in the moment.

So what do they need? More face-to-face time. Not just technical drills (think, “please give the interpreters hosting privileges”), but real human interaction—spaces where they can build confidence, find mentors, and practice connecting beyond the screen. Because whether you’re in a boardroom, a classroom, or a Brady-Bunch grid on Zoom, presence is the thing that makes the work land. And if the Wi-Fi drops? Well, presence is your only backup plan.

Have you ever witnessed or experienced burnout due to the emotional weight of certain assignments? How do you process or recover from those moments?

Tiffany: I wouldn’t say I’ve witnessed burnout tied to one specific type of assignment. It’s more the cumulative weight of the work itself. As practitioners, we’re not exactly known for taking care of ourselves. The job demands a lot mentally, emotionally, and physically. Back-to-back assignments, the travel in between, preparing, debriefing, and then still having to show up fully—it all adds up. And that’s before you factor in home life, family, or personal challenges we push to the side to focus on the day.

Part of the struggle is balance. Knowing when to accept a job, when you’re at your max, and how to manage the guilt of saying no. Too often, self-care gets postponed. We grab fast food because it’s quick, skip exercise to sleep a little longer, and before you know it, the nonstop “go” has us completely out of alignment. When that happens, we shut down.

What helps is proactive scheduling. You don’t have to be a staff interpreter to find balance—you just need intentionality and planning. Book work in advance based on your income goals or ongoing clients, then deliberately leave space for last-minute requests. Build in time for meal prep so fast food isn’t your default. If your calendar is packed with all-day jobs or travel, mix in a few shorter assignments to make space for exercise, a walk, or even a massage. And sometimes, the answer is simple: say no, stay home, and sleep.

What does allyship look like in the interpreting world, and how do we move beyond performative gestures?

Tiffany: This is a layered question. If you ask ten different people what allyship looks like, you’ll likely get ten different answers. It also depends on which part of “the interpreting world” we’re talking about—Deaf interpreters, hearing interpreters, interpreters of color, and so on. Allyship won’t look the same across all those groups.

One of the problems is that we get stuck on terminology. New words and paradigms can be helpful because they give language to experiences, highlight inequities, and spark discussion. But they can also become boxes to check—a way to avoid negative labels rather than a call to meaningful action. Most people want to be seen as “trying,” which is understandable. The risk is that it stops at appearances.

For me, allyship comes down to sincerity and intention. It’s not about memorizing a definition or using the term to criticize colleagues. It’s about practice: actively asking, “In what ways can my skills serve someone else? How can I advocate for them in this moment?” Real allyship is a conscious, ongoing choice—it takes time, effort, and consistency.

How do you prepare yourself to interpret for Deaf individuals whose cultural background or lived experience differs significantly from your own?

Tiffany: Honestly, I think the question almost answers itself. The best preparation happens in how we live our daily lives. You don’t have to be an expert or a know-it-all. You just have to be curious, selfless, and sincere.

Striving to be skilled, kind, flexible, and nonjudgmental—while keeping access at the center—makes us stronger professionals and more whole humans.

If we’re living with openness, our personal circles should already include people whose backgrounds and experiences are different from ours. That exposure alone is an education, and it strengthens our ability to interpret for anyone. Striving to be skilled, kind, flexible, and nonjudgmental—while keeping access at the center—makes us stronger professionals and more whole humans.

We should always want to expand our understanding of people. That can look like traveling to unfamiliar places, reading books, watching documentaries, or simply striking up conversations in everyday spaces like coffee shops or parks. (Safely, of course!) All of these experiences build the cultural awareness that makes us better interpreters—and better connected human beings.

What has this profession taught you about communication, trust, and human connection?

Paris: This profession taught me that communication, trust, and human connection aren’t built in stages—they happen together. And for me, the key has always been curiosity. Not just curiosity about language, but about people, power, and what’s really happening in the room. That kind of curiosity kept me from accepting “this is just how it’s done” as the final answer.

Now, let’s be honest: a lot of the ethics and professionalism in our field were written through a white lens. That shaped what was considered “appropriate” or “neutral,” and it left whole parts of humanity outside the frame. When I leaned only on that framework, I showed up smaller, flatter. But when I started leading with presence, culture, and authenticity—when I let my personality show—I started building actual community, not just ticking off ethical boxes.

Our presence gives it life. And the future of this work, I think, is in holding both: honoring the rules while daring to show up whole.

That doesn’t mean throwing the handbook out. Standards matter. Guardrails matter. But connection happens when we bring the human into it. The handbook gives us a baseline. Our presence gives it life. And the future of this work, I think, is in holding both: honoring the rules while daring to show up whole.

Tiffany Hill is a Washington, DC/DMV native. She was born in the District of Columbia, Washington, D.C. and raised in the Metropolitan Area where she is the founder and owner of a boutique interpreting firm, First Choice Interpreting Service, LLC. In addition to running her firm, she works as a Freelance, trilingual (Spanish) Interpreter and Interpreter Mentor. As a self-proclaimed “couch scholar,” she has a heavy passion towards expanding our human capital through dialogue and meta analysis, with a strong emphasis on improving and enhancing the field for Black, Indigenous, People (Interpreters) Of Color. When she is not in the gym and hiking hills, she is traveling the world and reading books. Usually at the same time.

Paris McTizic is currently an ASL/English interpreter in the Washington metropolitan area. He is the CEO and owner of The McTizic Interpreting Experience, LLC, and serves as a mentor to emerging sign language interpreters nationwide. His journey has led him to interpret in a multitude of settings including academia, government, video relay service, and NETFLIX to name a few. Paris is deeply passionate about creating space and uplifting communities of color. He aims to continue to provide access for Black and Brown Deaf people for years to come.

Paris McTizic and Tiffany Hill, founders and hosts of Terp Tap In, continue to create thought-provoking conversations on their Instagram page. Follow their work and join the dialogue here: instagram.com/terptapin